Just after sunset on an October evening in 1408, six years into the reign of the Ming dynasty’s Emperor Yongle, Chinese court astronomers spotted a mysterious new star glowing high in the southern sky, near the heart of the Milky Way.

“It was about the size of a cup-shaped oil lamp, with a pure yellow colour, smooth and bright,” according to Hanlin Academy scholar Hu Guang, in a formal report to the emperor that interpreted its appearance as a heavenly endorsement.

“We, your ministers, have encountered this auspicious sign, and respectfully offer our congratulations ... This splendid omen is truly a sign of an enlightened era,” Hu wrote, praising the ruler whose sweeping ambition had launched Zheng He’s treasure fleets and extended China’s reach as far as Africa.

“The star remained stationary and calm over 10 days of measurement and observation,” he noted, in a rediscovered memorial that has settled a long-standing debate among modern astronomers about the true nature of the 1408 event.

While earlier records were too brief to draw firm conclusions, this official account confirms that the phenomenon was a nova – the slow, temporary brightening caused by a dying star – rather than a comet or meteor flashing through the sky.

The discovery was reported last week by researchers from China, Germany, and Chile in peer-reviewed The Astronomical Journal. The unprecedented details, including the star’s size and brightness, also helped the team to narrow down the star’s possible position.

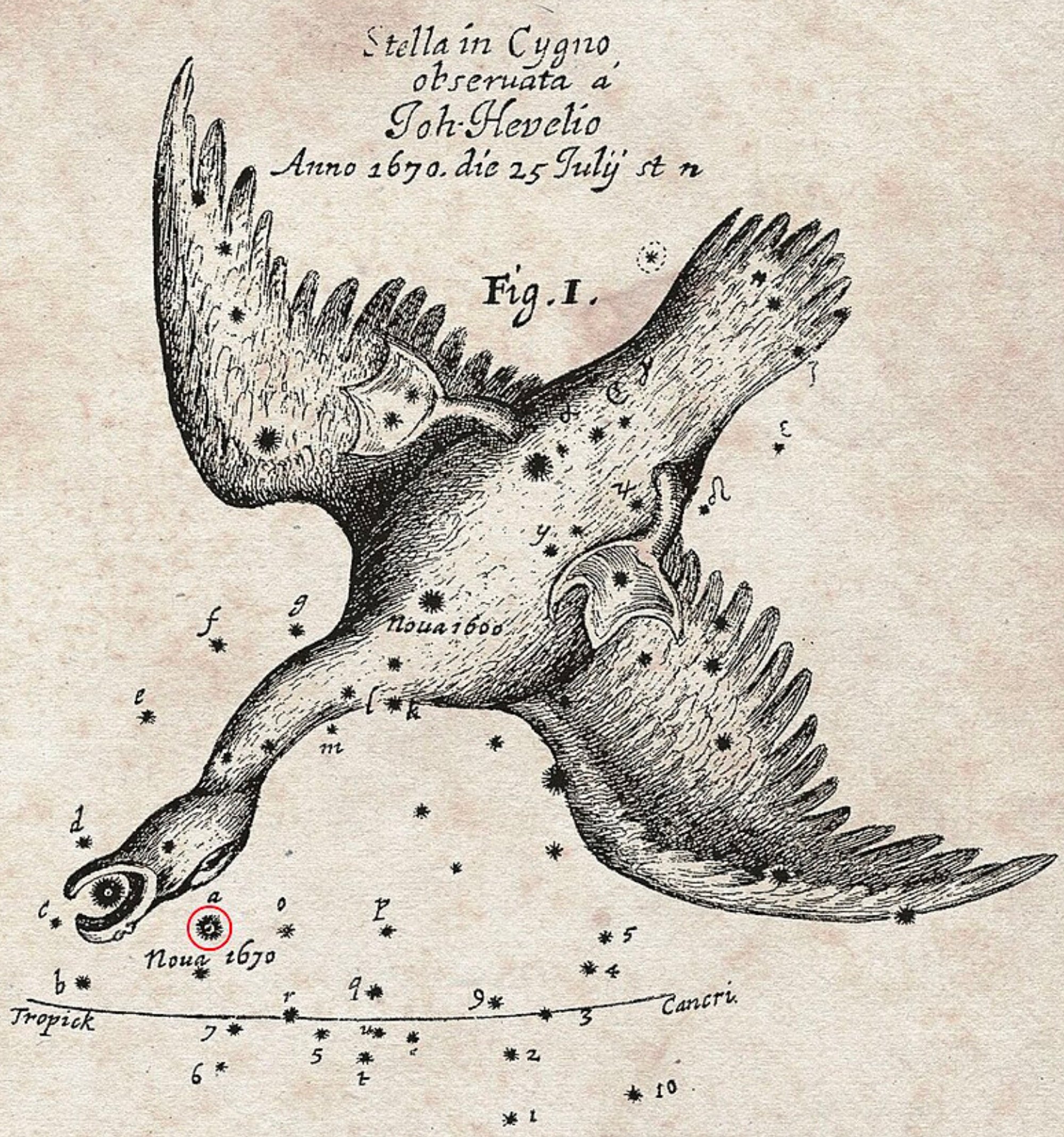

The astronomers’ analysis pointed to a stellar remnant named CK Vul, located between the modern constellations Cygnus and Vulpecula, as the most probable aftermath of the 1408 nova.

Co-author Suzanne Hoffmann, from the University of Jena in Germany and the University of Science and Technology of China in Hefei, said the team hoped the paper would spark the interest of observational astronomers.

None of the authors currently has access to telescope time, so they are unable to follow up on CK Vul and other candidate objects, to confirm whether their assessment is correct, she explained.

Hoffmann said that such collaborations are common in science, pointing to the discovery of Neptune in 1846 as an example. French mathematician Urbain Le Verrier predicted its existence and calculated the position, but had no telescope.

Le Verrier sent his calculations to the Berlin Observatory, where astronomers spotted Neptune, within just 1 degree of the predicted location – about the width of two full moons side by side in the night sky.

According to Hoffmann and her colleagues, the star that caused the 1408 nova would have lived on as a white dwarf – the hot, dense core left behind by the death of a star like our Sun.

More than 250 years later, it is likely to have merged with a companion star, in a dramatic event that led to the 1670 eruption now associated with CK Vul, the researchers wrote in the paper.

However, CK Vul is hidden inside an opaque shell of dust and remains difficult to observe. Hoffmann said astronomers could still search for faint traces of the ancient eruption –such as expanding gas shells or glowing filaments – using infrared or X-ray telescopes.

Over a span of more than 2,000 years, astronomers in ancient China carefully recorded celestial events, tracking everything from “guest stars”, as temporary bright objects were termed, to comets and eclipses with remarkable accuracy.

One of the best known examples is the Crab Nebula, the remnant of a supernova explosion recorded by Chinese astronomers in 1054 as a brilliant “guest star” that shone even in daylight for weeks and remained visible at night for nearly two years.

Nearly a thousand years later, modern telescopes linked that ancient sighting to a glowing cloud of debris 6,500 light years away, showing how centuries-old records can still guide today’s astrophysics discoveries.

-- SOUTH CHINA MORNING POST